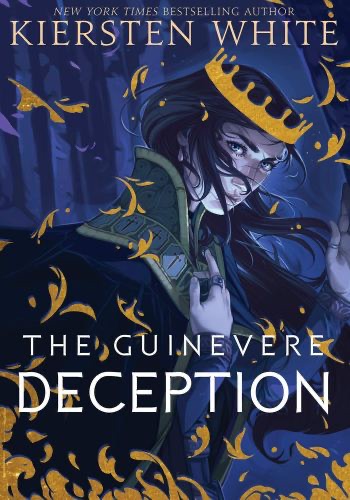

The Camelot Rising Trilogy – Book Review

This book just queerbaited me, and I really almost fell for it. The Camelot Rising trilogy is a YA Fantasy series by Kiersten White that reimagines Arthurian legends through a feminist lens.

The Camelot Rising trilogy is a YA Fantasy series by Kiersten White that reimagines Arthurian legends through a feminist lens.

Summaries

The Guinevere Deception

The first novel opens by introducing Guinevere, a magically created double for the real Guinevere, a dead girl, that our main character must impersonate. Guinevere is betrothed to King Arthur and sent by Merlin to act as his magical protector. Guinevere must navigate court politics, her growing feelings for Arthur and Mordred, and her complex parental relationship with Merlin… all without revealing her false identity.

The Camelot Betrayal

The second novel centers around Guinevere’s struggles with identity, the aftermath of Mordred’s betrayal, and a new girl in Camelot claiming to be Guinevere’s sister. Merlin’s influence over Guinevere continues to remain a threat and her past resurfaces in unforeseen ways. Guinevere has been experiencing terrible nightmares, threatening the destruction of everything she holds close.

The Excalibur Curse

The final novel of the trilogy unravels the knots holding the mysteries of Camelot together, all centering around the infamy of Excalibur and the reign of the Dark Queen. Guinevere must make a choice between tradition and progress and fight for who she loves.

Reviews

As a preface, I think it should be said that I am not the target age group for this novel. However, I also think that the series speaks down to its readers in a way that ostracizes them from the themes it’s attempting to convey.

This series attempts to be a feminist retelling, fit for teen girls dreaming of strength and capability. And yet… it features an incredibly weak main character. Sure, Guin may be a far cry removed from the Guinevere of legend, but she still isn’t up to modern qualifications for strong females in YA Fantasy.

Arthur takes on the “strong protector” role many male Romantasy leads do. This means that Guinevere is constantly out of the loop for important information, kept locked away in Camelot while the action takes place elsewhere, and only has the ability to take agency about who she loves.

That… does not sound very feminist.

I would like to be able to tell you that those issues only pervade the first book, and Guinevere develops into a magical politicking powerhouse. But she consistently makes the same mistakes without learning from them over three books (young people learning from mistakes is crucial in good YA Literature). Every book seems to center around the same plot of “Guin thinks there is danger but only ends up making things worse” and “Guin is held back from stopping danger by Arthur.”

The Guinevere Deception

This book has what is likely to be the cringiest opening line of any book I’ve read. Though, as any good opener does, it sets the stage for the rest of the novel.

There was nothing in the world as magical and terrifying as a girl on the cusp of womanhood (Chapter One).

I genuinely believe that if I read this at 16, the age Guinevere is and the age I bought this book, I would have had the same reaction I had as an adult: an eye roll and a groan.

I may have wanted to be magical and terrifying at 16—I still do, who doesn’t?—but if someone verbalized it to me in such a heavy handed way, I would have firmly rejected the idea. Which might explain why it took me 6 years to read this book after buying it.

I think the first line showcases what I mean when I say that these books speak down to their audience. Teens don’t want to be told they’re special, they want to be special. There is a difference between patronizing language meant to lift someone up and truly compelling themes and character actions meant to enrich younger generations. The Guinevere Deception largely hits the former rather than the latter.

Guinevere’s character also exemplifies the issues I take with this novel intending to be a feminist retelling of Arthurian legend, because she still mostly takes up the role of a damsel. Guinevere is magically hydrophobic, tied back to her upbringing by Merlin, and half the time it seems someone is carrying fragile Guin across water.

Arthur and Mordred treat her as if she is a piece of glass that will shatter at a moments notice, and frankly they’re not even wrong—Guinevere has a penchant for getting herself into trouble and poor decision making.

Now, let’s get to the ways that Arthur fulfills the typical male Romantasy character role, and how that ruins the feminist themes of the novel.

Arthur seems to be more interested in his duty to Camelot than his wife, leaving Guinevere at arms length for the most part. Remember Arthur is also supposed to be the end game love interest and he is as bland as a vanilla wafer. Arthur has the problem of his words conflicting with his actions. He wants to be Guinevere’s protector, yet always seems to be leagues away from her. How can you love and protect someone you barely know or take any chance you can get to be away from?

Mordred, the twist betrayer (it wasn’t very twisty) at the end of the novel, is a far more compelling love interest than Arthur. In my opinion, if the secondary choice is superior to the first, there is something up with the book. Mordred fits the tall dark and handsome bill, with conflicting loyalties and a magical past—far more similar to Guinevere than her husband. He attempts to give Guinevere some semblance of agency and employs her to choose for herself, as long as the choice is him, of course.

Arthur does not allow Guinevere to act independently. He treats Guin as a symbol of queenly duty and is fearful of magic, therefore making her incapable of expressing her true nature or interacting with courtiers in the manner she pleases. Arthur does not allow himself to be emotionally connective with her, unlike Mordred. Finally, Arthur and Guinevere seem to constantly miscommunicate information, leading each other to false conclusions.

Considering the endgame nature (sort of, we’ll get there in book three) of Arthur and Guinevere’s relationship, I think it sets a poor example for the types of relationships young people should invest in. Guinevere choosing Arthur shows young women that their partners might very well be emotionally distant, restraining, and infantilizing—and that they should be fine with that.

The culmination of this book focuses on the return of Merlin as he attempts to assert control over Guinevere and unleash the terrifyingly magical girl she was made to be.

It’s all a test of Guinevere’s agency and ability to think for herself. On paper, that is a great way to discuss feminist themes.

In practice, that really just looks like Guinevere choosing who controls her: Merlin or Arthur. Obviously, she chooses Arthur who gives her a thin veneer of agency over Merlin who wants all of it.

But, by choosing Arthur and breaking Merlin’s hold over her, Guinevere breaks the magical safeguards around Camelot, allowing magic to seep back into the realm. And, more importantly, setting up the heightened conflict for the next book: the cleverly named Dark Queen.

The final magical showdown further shows why I think this book falls flat in the theme department, because is it really feminist if she’s still under the control of anyone but herself? Is it really groundbreaking if she’s still choosing between two men (three with Mordred)?

The Camelot Betrayal

This is Guinevere’s Not Like Other Girls arc.

Guinevere’s opinion of herself seems to vacillate between two memes: I’m Just a Girl and I’m Not Like Other Girls.

These two sides of girlhood aren’t inherently bad. Quite understandable even, because many girls go through similar crises of identity, questioning whether they want to go with or against the grain of society. But the book conveys this struggle on the same, heavy handed level of I’m 14 and this is deep, when teens are capable of so much more than the emotional depth of a meme.

Guinevere’s Not Like Other Girl’s arc is best shown through her relationship to her sister.

A big plot point in this book is the introduction of Guinevach, the sister of the real Guinevere, who is instantly liked in court far more than her obnoxious sibling.

Guinevach is everything Guinevere isn’t: open and honest with people, unrestrained by secrecy and fear, and liked by everyone. Naturally, Guinevere takes all of this as some elaborate ploy by dark forces and keeps her sister at arms length.

Guinevere has reason to be suspicious, since she has been experiencing troubling dreams. But nothing ties Guinevach to the dreams other than her appearing around the same time.

I don’t quite know if you could call it a trope, but I’m really over the whole “main female distrusts new female because people like her/she’s new” plot point. It’s exhausting.

Guinevere consistently assumes shenanigans are afoot, leading to her own downfall in every book. This is what I mean when I say that Guinevere doesn’t learn from her mistakes, she’s a terrible judge of character and a poor decision maker despite all her overthinking. Pushing Guinevach away made Guinevere disliked at court, and when you’re the queen, that’s just poor politics. Not to mention she emotionally manipulated her sister for an entire book, only serving to make herself overthink more than necessary.

Because shocker the girl is harmless and only wants to know the truth about Guinevere. Her presence is a red herring to distract Guinevere from real danger with Mordred (AGAIN) and the Dark Queen. Once more, putting Guinevere into a situation where her judgement was completely misinformed and fueled by her own hyper-vigilance.

The scene where Guinevere reveals her fraudulent identity to Guinevach is a heartbreaking because you realize that she was genuine and treated like shit for nothing.

After that, the pair act all hunky-dory as if everything is fine. Woohoo. It doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, and Guinevach seems far too accepting of the situation, leaving the whole plot thread feel unsatisfying and somewhat useless. Hence why this book feels a bit like a filler episode as we wait for the plot to happen.

Speaking of another situation where Guinevere saw danger when there was none: the mysterious knight.

That knight turns out of be Lancelot, and as a subversion of Arthurian legend, is a woman. Considering the classic love triangle between Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere, I thought I was in for what could be the captivating story.

Like most of my hopeful assumptions, I was wrong.

There is a sort of underlying romantic tension between Guinevere and Lancelot that ultimately goes nowhere. Lancelot follows Guin around to “protect her,” they get a few scenes which border on longing for each other, and that’s it.

Lancelot left me feeling very frustrated because there is clearly a lot which could be done with her character that was left untouched. As “subversion of classic tales go,” altering a character’s gender can open a lot of doors for storytelling.

The novel makes Lancelot out to be a Brienne of Tarth-esque character, wanting to prove her strength in a man’s world. Lancelot is said to be one of the best swordsmen in all of Camelot, but has gone unnoticed due to her gender.

For the most part, Lancelot hid her feminine identity in order to fit in. Guinevere knights Lancelot and she is lifted up as a member of Arthur guard.

The really spicy stuff (not that type of spicy, calm down) is with Mordred, who consistently serves as the most compelling character amongst all these bland vanilla wafers. He always offers Guinevere a way out when she is feeling most vulnerable, except he does so in a manner that seems to be for his own fulfillment and not hers.

The Excalibur Curse

Opening the book, we get some confusion from Guinevere about which side of the girlhood meme spectrum she lands on.

She tried to hold on to both thoughts at once: her power and her smallness, each a comfort in its own way. She was only one girl, after all, in a world full of them (Chapter One).

The Excalibur Curse is the culmination of the Dark Queen’s tirade of evil in Camelot, and yet, the book mostly focuses its efforts on Guinevere’s romantic struggles. So, I will as well.

I do have some lingering questions regarding Arthur that left me a little dumbfounded while reading. How old is he? Supposedly, he was 18 in the first book. And yet, he’s already got an entire kingdom, a dead wife, and a child? I get that all of these things are technically possible, but its just another instance of a greater issue within YA literature where characters have the life experiences of someone in the 30s, yet they’re barely old enough to leave high school.

The final showdown of this novel is a ploy over Arthur in order to lead him out of Camelot by convincing him that his son is still alive. And completely within character, Arthur locks Guinevere in the castle as he goes off to rescue his child. Turns out, double ploy, it was really to lure Guinevere out of Camelot and thus lower the kingdom’s magical defenses, because she is incapable of standing idly by when someone needs help. Everyone other than her seems to be aware of that fact, which is shocking considering similar miscommunication and hyper-vigilance played a part in the final showdown of all three books.

Arthur completely ditching Guinevere for a symbolic representation of his previous relationship feels like icing on the cake for my Arthur hate train. He disregards her on numerous occasions and it really just makes me angry since he’s supposed to be the “right answer.”

And the person Guinevere realizes is truly the “right answer,” the person she comes to realize understands her entire being is Lancelot.

I got to two-thirds of the way through the book and was elated that we finally get some semblance of payoff for all those romantically charged scenes between Guinevere and Lancelot. But they go nowhere!

This book just queerbaited me, and I really almost fell for it. I was so hopeful that Guinevere would follow her heart and ditch all the men trying to control her, but she doesn’t.

Guinevere decides to choose Camelot, rather than a specific person.

White was certainly trying to make a feminist statement with this resolution, that much makes sense and fits with the themes of the novel. But it ends up blurring the themes more, in my opinion, because it’s putting Guinevere back into a position where she’s pining over the emotionally absent Arthur.

The ending doesn’t read as if Guinevere is staying in a open political marriage with her love Lancelot on the side. It’s a return to the status quo, where Guinevere hopes for her blossoming love with Arthur and Lancelot by her side as her sworn sword.

Whatever led to their marriage, whatever it became, she loved him. (Chapter 50).

While there was a clear attempt to adhere to feminist themes, it feels a bit muddy if Guinevere is blocked off from her preferred choice: Lancelot.

Guinevere continues to admit Lancelot is the best answer up until the final scene, but readers are queerbaited by never having an admission of said feelings.

Even though she was no longer magic, Lancelot’s hand in hers still felt right in a way that could not be denied. (Chapter 51)

Except we, as readers, are denied. We only get sly mentions at the possibility of love.

Duty, passion, love. She had known the first two with Arthur and Mordred. She could wait patiently to see what the third became. (Chapter 51)

It seems to be implied that love will be Lancelot, but considering Guinevere wonders about what her marriage with Arthur will turn into… it seems intentionally up for interpretation.

As Guinevere stands hand in hand with Arthur and Lancelot during the final scene, an overall air of annoyance could be felt within me. This series led me on in so many different ways, from the queerbaiting, miscommunication plots, and a main character who never seems to learn, I was left terribly unsatisfied.

For a series attempting to navigate a love quadrangle, it’s all very non-committal.

Some part of me also felt like there were slight polyamory undertones in that final scene, Guinevere may have chose Camelot, but the book makes it seem like she chose both Arthur and Lancelot. All the more frustrating considering how much it attempts to return to the status quo.

Arthur took Guinevere’s hand. Guinevere reached out her other hand and took Lancelot’s. (Chapter 51)

In a similar manner to the beginning of the story, the book ends placing girls as the most powerful beings known to humanity.

Now she would make the choice to serve it for as long as she could, however she could, as the most powerful thing she could be. A girl. (Chapter 51)

So, Guinevere is just a girl but that’s what makes her special because girls are powerful. Just as the series began with a heavy handed remark for female empowerment, so it ends.

Conclusions

These books are romance first fantasy second.

Most of the fantasy realm goes unexplained unless it’s strictly necessary for the plot to unfold. It seems there is a level where White expected the reader to have a base understanding of Arthurian legends, which might have been an oversight. The magic system isn’t explained and sometimes waved away with it’s magic.

The romance, while giving some interesting options between Mordred, Arthur, and Lancelot, ultimately doesn’t commit to any singular person in a manner which could be unsatisfying to some readers—certainly it was for me.

The writing of the series is very tell don’t show, featuring some very heavy handed theming. The mix of telling and not showing combined with half-assed feminist themes gives off the sense that the book is talking down to its audience.

Speaking of feminism, this series seems to be a little confused about what exactly that means. While Guinevere does get the chance to take agency and make choices, they usually fall flat due to misogynist romantasy pitfalls. Namely, Arthur’s entire archetype as the emotionally distant love interest that women swoon over for some reason, and Mordred urging Guinevere to choose herself, but only if that choice is him.

Finally, if you’re looking for queer representation, this series is far from it. We’re led along to think that Guinevere will choose her own feelings for once and be with Lancelot, but nothing comes of that and we’re left queerbaited. The outwardly queer characters are relegated to servants and people who die for the plot. Lancelot is never explicitly said to have any sort of LGBTQ identity, despite being heavily coded to read that way.

Overall, this series left me angry, frustrated, and wishing I left it in my TBR pile.